Total Eclipse: Lee Lozano’s Energy Paintings

Helena Vilalta

On the night of April 12, 1968, New Yorkers were treated to an unusually clear lunar eclipse. Shortly before midnight, a round, full moon entered the earth’s shadow. For about an hour, its darkened surface took on a copper glow, as only the longer wavelengths of red and orange light made it through the earth’s atmosphere.1

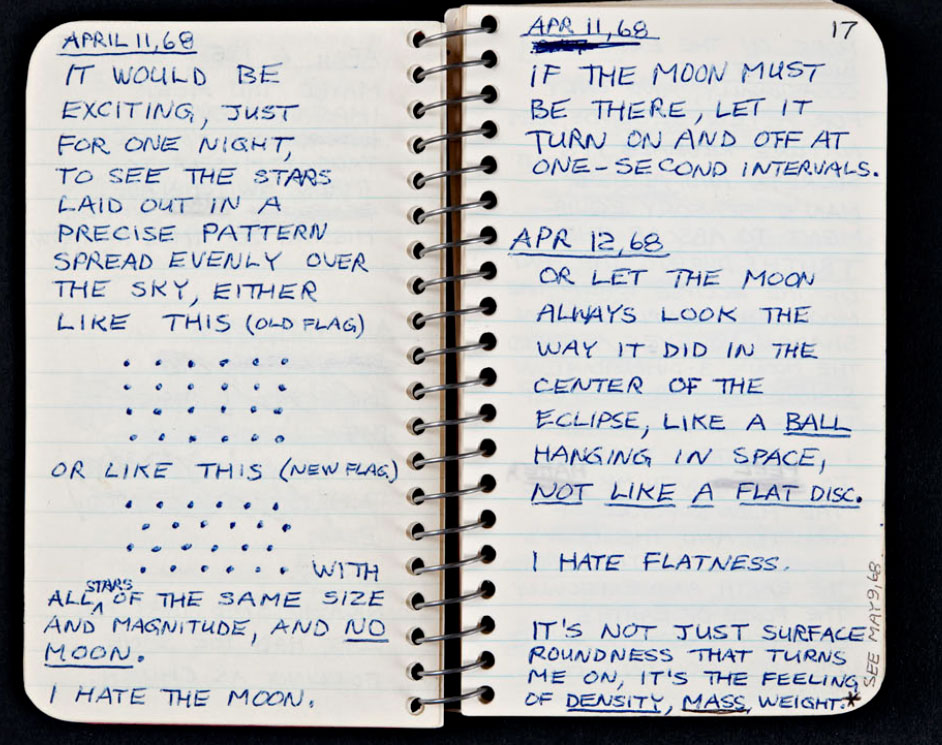

fig. 1 Lee Lozano, interior pages of Private Book 1, 1968.

The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Among those watching was the artist Lee Lozano, who committed the experience to writing: “During the part of the eclipse when the moon was completely in shadow, my eyes absorbed the moon’s 3-dimensional roundness for the first time.” “Roundness” held pride of place in her aesthetic vocabulary, as opposed to the “flatness” she loathed in painting. “I hate flatness,” she wrote on the night of the eclipse. “It’s not just surface roundness that turns me on, it’s the feeling of density, mass, weight”2 (fig. 1). A few days later, she would continue: “‘Mass’ contains the idea of inertia, which contains the idea of acceleration, which contains the idea of movement. The movement of an object of large mass (e.g. the moon) rather than an object of small mass (e.g. a bullet) is exciting to me. The greater the mass, the more monumental the movement. Art does not need to be monumental, but movement (change) does.”3

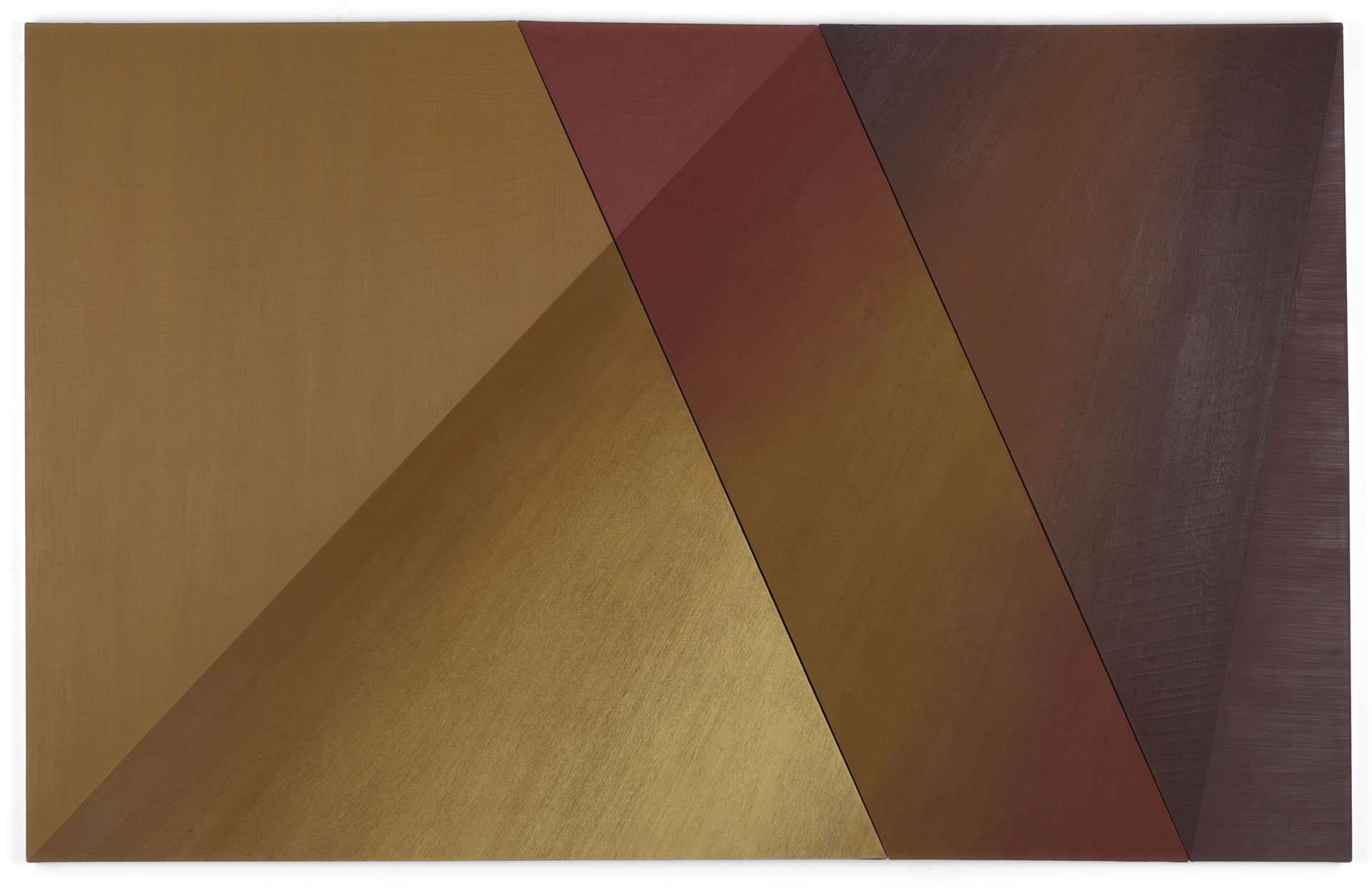

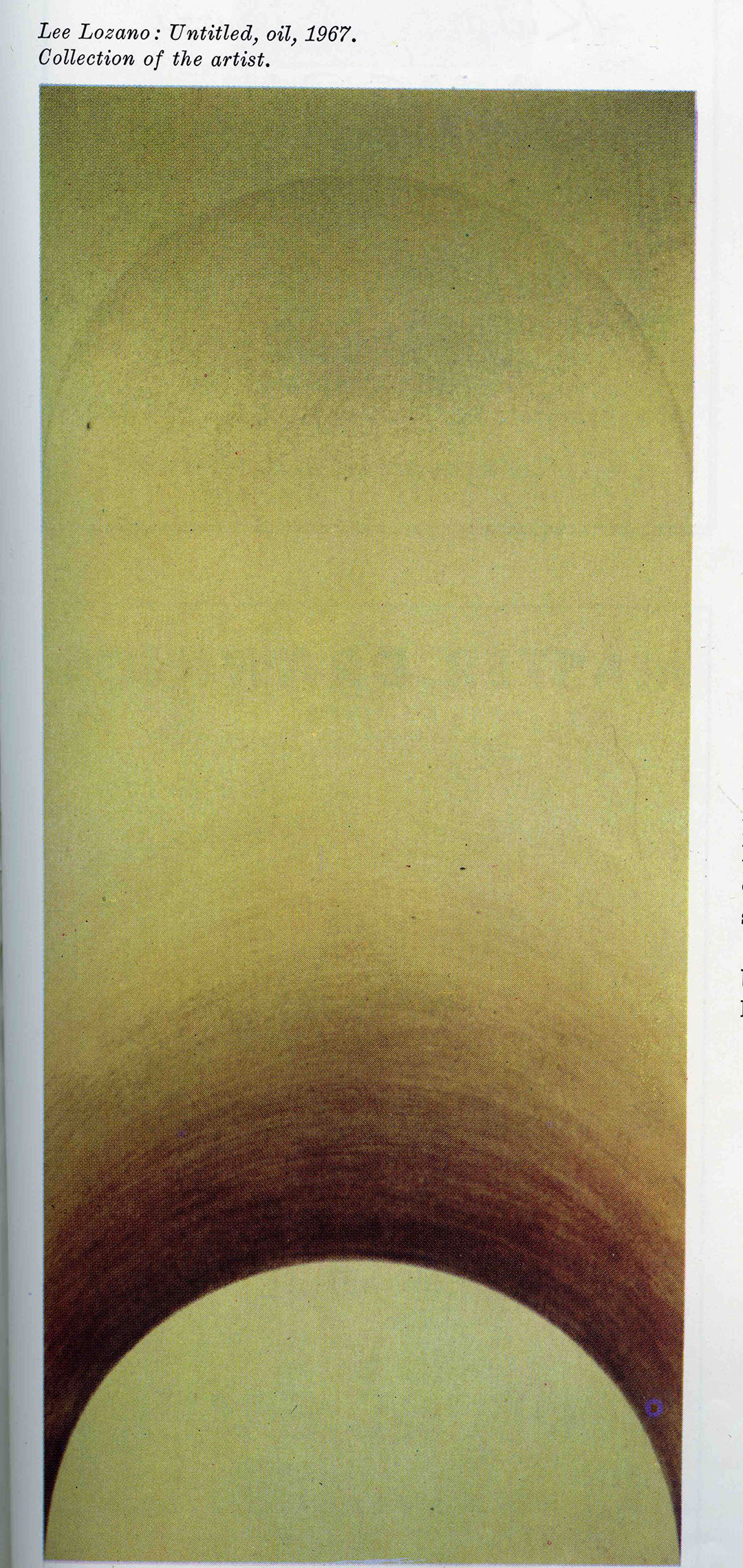

fig. 2 Lee Lozano, No Title (1967), oil on canvas, 244 x 107 cm. Austrian Ludwig Foundation, Vienna. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

The distinction that Lozano was establishing here, between the movement of small and large objects, bullets and celestial bodies, speaks to key developments in her painting around the time she made No Title (1967, fig. 2), now in the collection of the Austrian Ludwig Foundation. She jotted these notes down having recently completed a three-year-long series of paintings, begun in 1964 and titled after verbs that denote physical actions. Early works in the series, such as Ream, Spin, Veer, Cross, Ram, Peel, and Charge (all 1964), depict close-ups of mechanical parts in motion. Initially, Lozano rendered the solitary screws, pipes, bolts, and drill bits in a gray palette, but as the series progressed, the forms became increasingly abstract and the chromatic range broadened.

fig. 3 Lee Lozano, Lean, 1966, oil on canvas, three panels, 198.8 x 312.9 cm overall. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Beginning in 1965, she was bolting together differently proportioned panels to create her large-scale paintings. Sometimes these sections delineate sequential fields through which geometric figures pass. In Lean (1966, fig. 3), a segment of a cone slants to the right, intersecting the central panel’s oblique edges as it traverses the chromatic spectrum from yellow to rusty red. In other paintings in this series, abstract bodies meet or collide across panels.

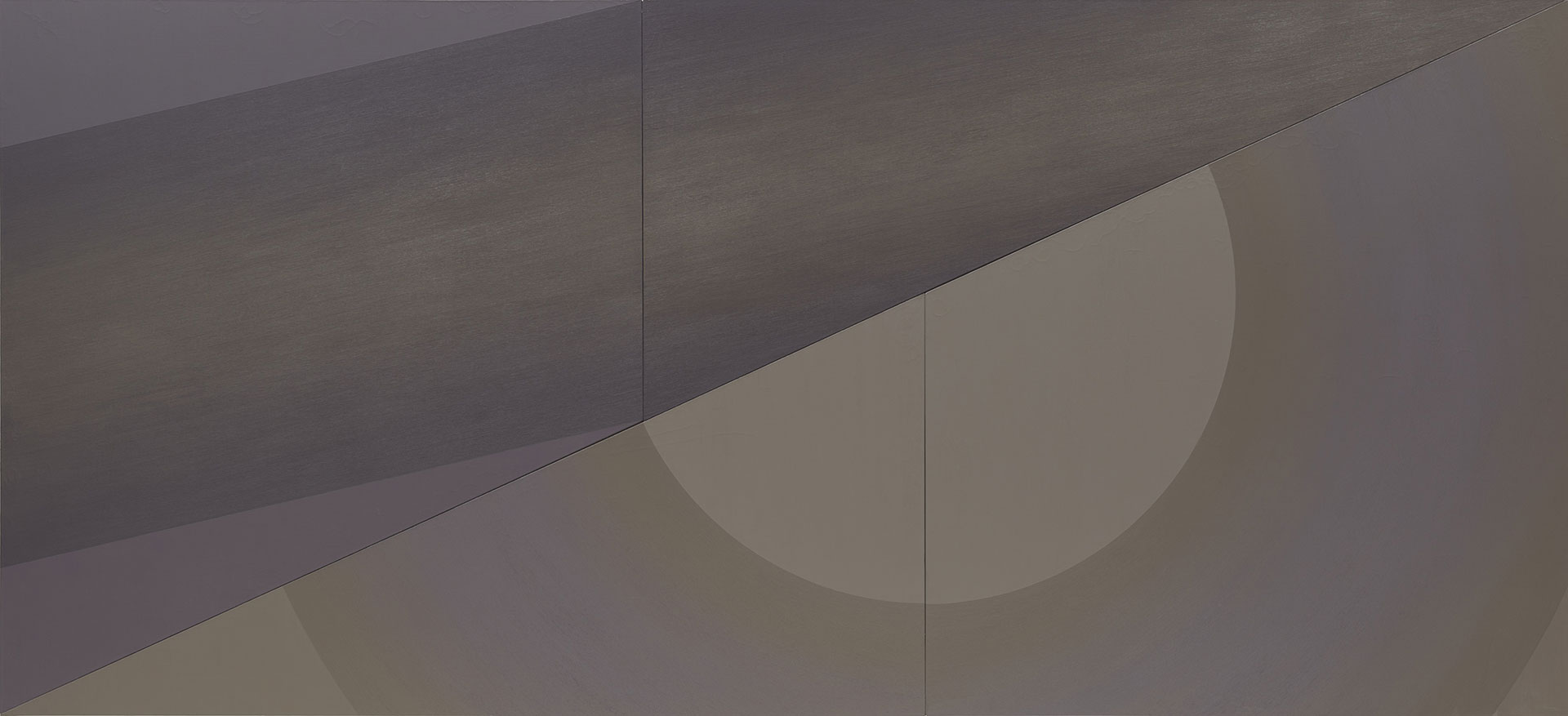

fig. 4 Lee Lozano, Breach, 1966, oil on canvas, four panels, 180.98 x 396.24 cm overall. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Corcoran Collection, Museum Purchase through the Director’s Discretionary Fund.

The diagonal cut that bisects the four-meter-long composition Breach (1966, fig. 4) traces a space of friction between two gendered forms: a purple-gray cylinder above and a taupe-and-violet half-ring below. Lozano called the forms “agents of speed and violence,” intimating that rather than depicting things in motion, she was conveying movement itself.4 When Bianchini Gallery exhibited a selection of these paintings in November 1966—marking Lozano’s first solo presentation in New York—critics commended the artist for compressing, “within a deliberately restricted range of forms, a ferment of energetic perception.”5

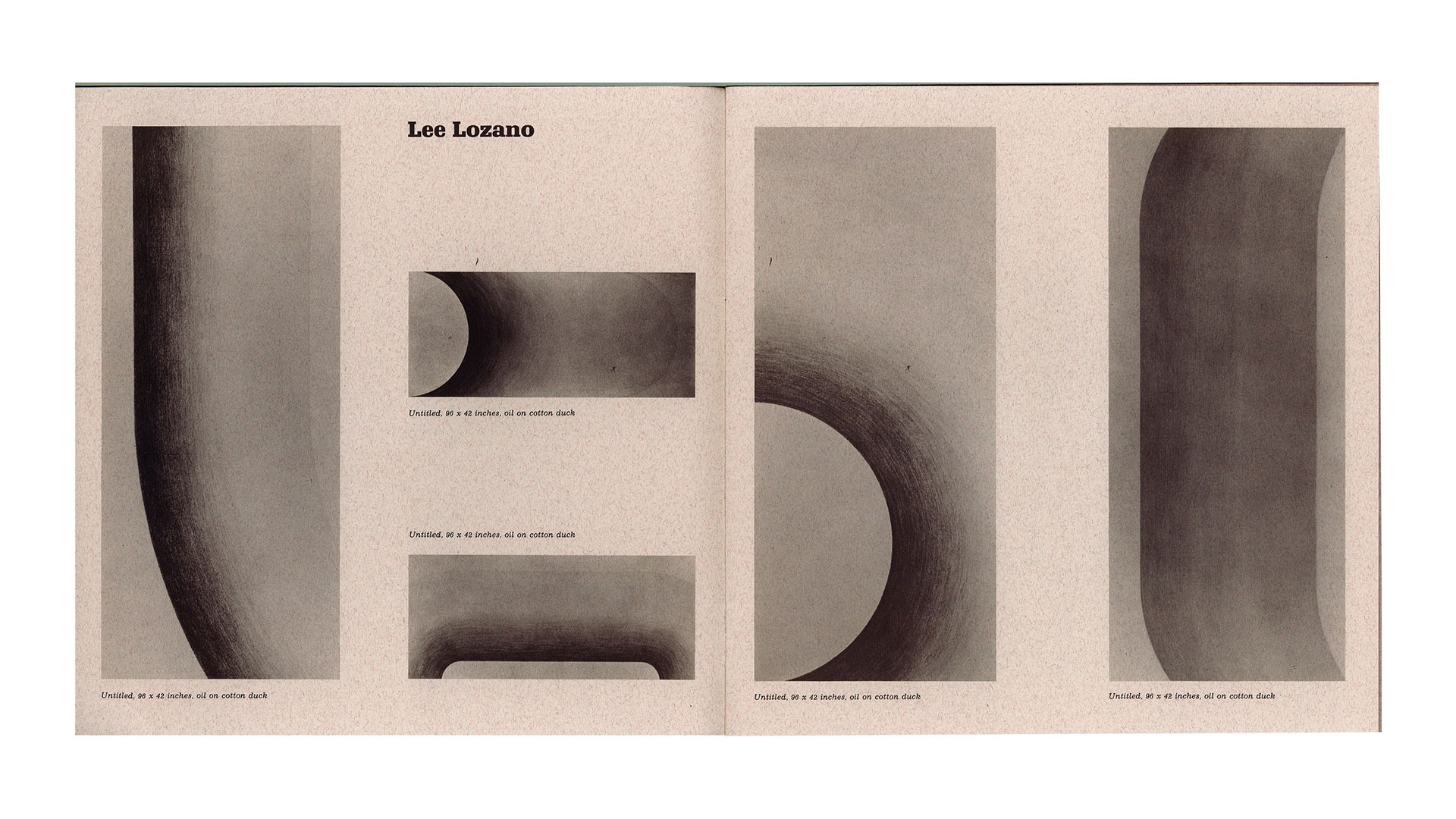

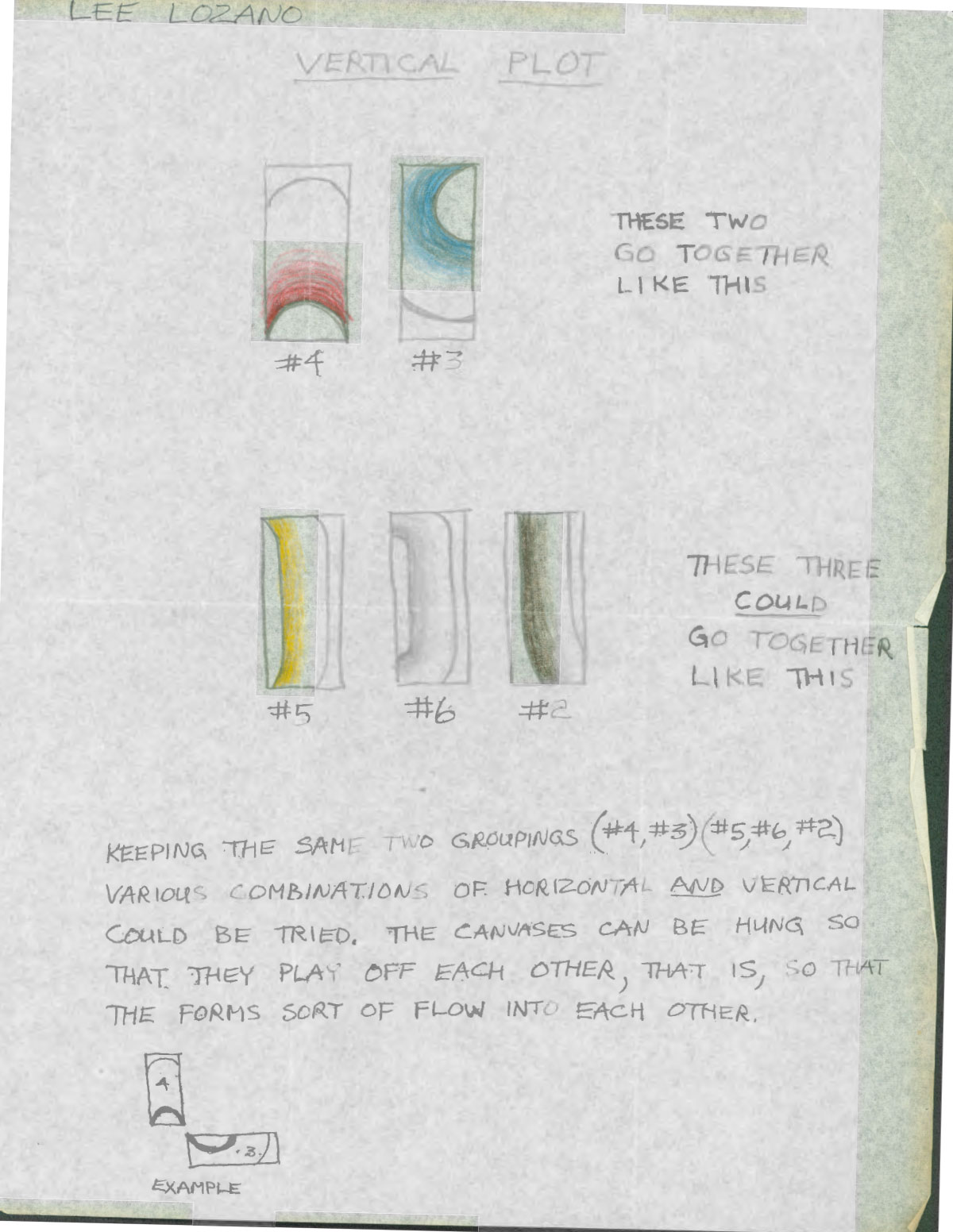

fig. 5 Lee Lozano’s double-page spread in the exhibition catalogue Gordon, Lozano, Ryman, Stanley (Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, 23 May–22 June 1968).

Lozano put an end to this extended series in May 1967, but continued to explore the capacity of painting to render a monumental sense of movement. The specific constraints of her next works included just two hues per painting (a base color and a top color for shading) and the use of uniformly sized, elongated rectangular canvases (each slightly bigger than a doorframe). Importantly, as well, from spring 1967 until she abandoned painting in 1970, she would depict curved lines only. As she put it: “In physics, all straight lines are really curved if you extend them far enough. And if you’ve been doing straight lines for a while, the next thing is to try curves. Where else is there to go but all the way around?”6 Five paintings from this new body of work (all No Title, 1967, fig. 5) were shown in 1968 at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, in a four-person exhibition of New York painting that featured Lozano, Robert Gordon, Robert Ryman, and Robert Stanley. (Lozano and her friends jokingly called the lineup “Three Bobs and One Lee.”7) Lozano gave Bill Leonard, the Center’s director, precise instructions to hang the paintings in two groupings: three paintings of cylinders with curved edges; and two paintings of semicircles.8

fig. 6 Lee Lozano, No Title, 1967, as reproduced in Art in America

(November–December 1968).

The latter pair included the work now with the Austrian Ludwig Foundation, in which circular emanations radiate out of a pale gray-green semicircle perched at the upper right of the vertically oriented canvas. Directional brushstrokes in the same base color trace concentric circles around the semicircle’s outline, extending all the way to the bottom of the painting. Lozano shaded the semicircle by superimposing wet-on-wet brushstrokes of ultramarine (the top color), raking the gray-green underlayer with a bristle brush to produce the surface’s finely grooved texture. But the illusion of volume is so subtle that whether the implied three-dimensional surface is convex or concave remains ambiguous: the viewer might see it as a section of a torus, or, alternately, as a passage leading toward a central opening. The painting’s companion piece for the Cincinnati exhibition is reproduced in a 1968 issue of Art in America (fig. 6), though its present location is unknown.9 The photograph shows a semicircle in light gray centered at the bottom of the canvas (its shorter width) and shaded in rusty ocher.10 Here, too, the directional application of paint suggests ripples emanating from a round shape, though instead of tracing progressively larger, concentric arcs, they trace parallel arcs moving upwards.11

The reproduction appears in critic Corinne Robins’s article “The Circle in Orbit,” which features statements by ten contemporary American artists who were turning to the circle as “a way to reflect on their own world, which is fast moving, fragmented, flooded with illusion—and which they would somehow like to see as whole and complete.”12 In her statement, however, Lozano emphasized her interest in endlessness rather than wholeness; she was fragmenting the circle, she noted, to encourage viewers to extend its radiating energy beyond the canvas.13

fig. 7 Letter from Lee Lozano to Contemporary Arts Center discussing possible installation options of her paintings for the exhibition ‘Gordon, Lozano, Ryman, Stanley’, c. 1968. Courtesy Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Echoing her own reflections on the roundness of the eclipsed moon, she rejected both flatness in painting and the idea of the canvas as a boundary: “I felt all I had to do is create a small part of the circle because the quality of illusionism in painting is what intrigues me—how far I must go to complete an idea. For me, each painting is part of a monumental form, so that all my paintings are just details of a form that can be extended to infinity or a point in infinity.”14 This idea was manifested in the unusual installation layout of her paintings within the Cincinnati exhibition. In a letter, Lozano encouraged Leonard to display the canvases in “various combinations of horizontal and vertical” orientations so that they would “play off each other, that is, so that the forms sort of flow into each other.” A diagram at the bottom of the page illustrates the painting in the collection of the Austrian Ludwig Foundation hung horizontally to form a right angle with its pendant piece, which is how the two works were finally displayed in Cincinnati (fig. 7).15

fig. 8 Lee Lozano, Wave series, 1967–70. Installation view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2017. Photograph: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores. Photographic archive Museo Nacional Reina Sofía. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

In suggesting that a ripple of energy could flow from one canvas to another, Lozano was implicitly modeling the paintings’ display on the motif of the wave form—the motif that would occupy her for the last three years of her painting career, as she completed her extraordinary series of eleven Wave canvases (1967–70, fig. 8). For this final tour de force, presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1970, Lozano would work within the same constraints—curved lines, uniformly sized canvases, two colors—to depict undulating bands spanning the length of vertical canvases. The progressively increasing wave frequencies embody her desire to paint a form extending to infinity like a ripple of “energy . . . not contained by the edges of the canvas.”16

In naming the series, Lozano cycled through loose synonyms, such as “bump,” “undulation,” “ripple,” “kink,” and “pulse,” before she eventually settled on “wave,” a term that resonated with a broad interest, among artists of the period, in the transmission and propagation of energy.17 Robins’s article notes how “art now strenuously insists that it is a relational experience, and the tension between the environment and the object has become an increasingly important condition of the work.”18 She illustrated this idea with a wall sculpture by Lozano’s friend Richard Serra, Two Cuts (1967), a piece of vulcanized rubber twice incised so that the rubber droops onto the floor in “slumping circular forms.”19 This expanded notion of process, which the art historian James Nisbet terms “energetic materialism,” occupied other artists in Lozano’s circle too.20 In their critical writings of the late 1960s, for example, Robert Morris and Dan Graham remarked on the ways art was being shaped by environmental forces beyond the artist’s conscious control, whether gravity, radiation, or audio feedback.21

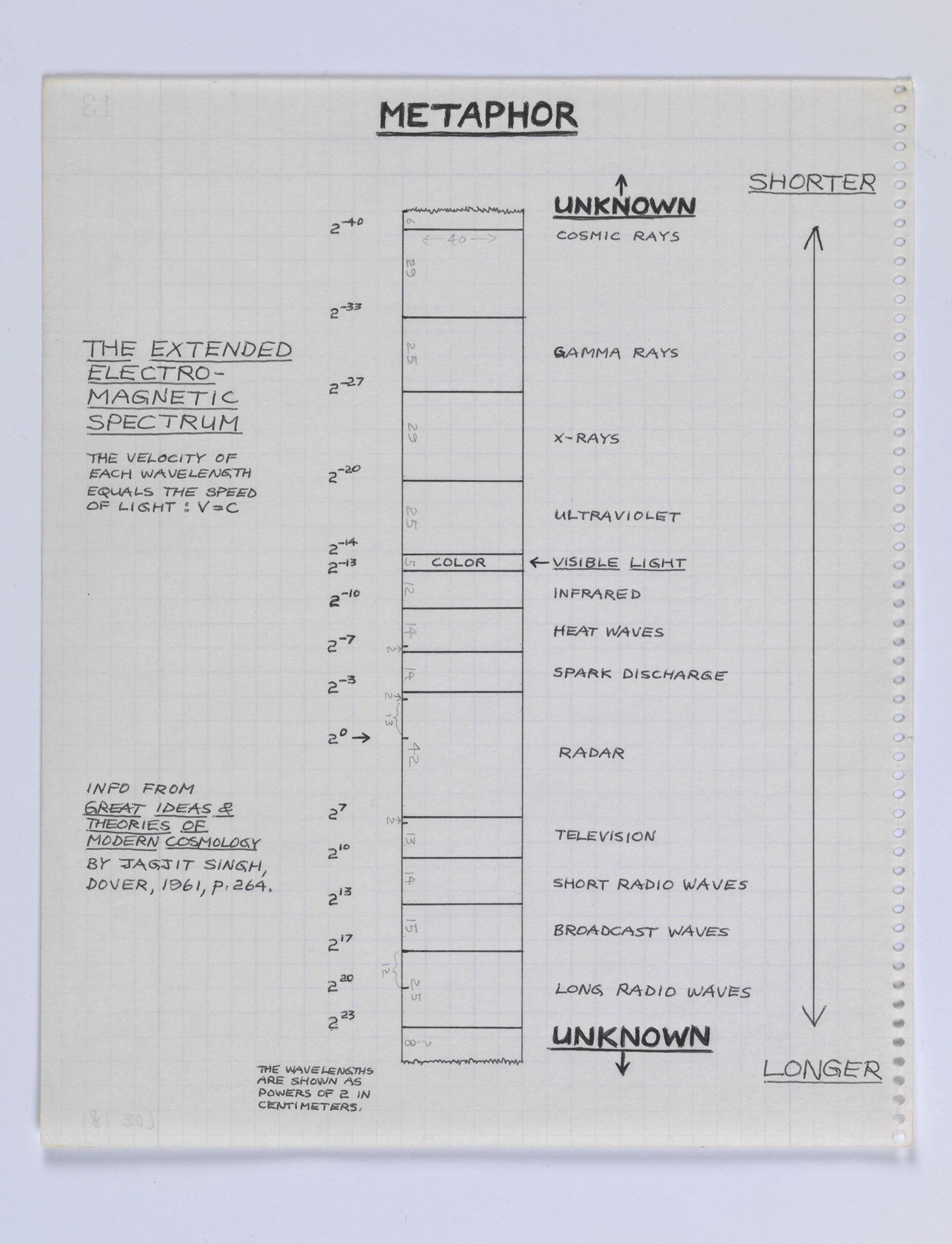

fig. 9 Lee Lozano, No title, undated, graphite and ink on paper, 28 x 21.5 cm. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

In Lozano’s Wave series, the concern with “energetic materialism” is inflected by her sustained interest in quantum physics. As her attention shifted from the movement of everyday objects to the cosmic energy of celestial bodies—remarked upon in her observations on the eclipse—her painting turned away from the depiction of human-centered motion to the representation of something like subatomic vibrations. Across the first ten Wave paintings, the frequency of the ripples depicted on each canvas increases gradually as the series runs through all the even factors of the number ninety-six (the longer measurement, in inches, of each rectangular canvas).22 This mathematical progression from lower to higher frequencies was also a progression from low to high intensity, as suggested by the display of a diagram of the electromagnetic spectrum (fig. 9) alongside the Wave series at Lozano’s 1970 Whitney exhibition. (The frequency of electromagnetic waves is directly proportional to the photon energy they carry—low-frequency radio waves have longer wavelengths and transfer less energy than the powerful gamma rays produced by nuclear fission.) After reaching the logical end of the series at the painting 96-Wave, however, Lozano added a final, unpainted canvas, 192-Wave, which bears just two flickering graphite lines. Jo Applin has aptly called it an “irritant”; that is, an outlier in the series’s numerical system, and, even more fundamentally, a deliberate short-circuiting of logic.23 In this light, the last unpainted canvas appears as a cipher for the surfeit of energy that painting cannot convey.

Lozano approached the making of the Wave series as one might a scientific experiment. She regularly recorded her “findings” in her notebooks, remarking upon the progression from matter to energy that the paintings convey, and describing how the series “gets more ‘real’ the longer the wavelength and more ‘unreal’ (non object-like) the shorter the wavelength.”24 The more intense charge of the later paintings is reflected in the use of color. Painted a deep red, 24-Wave marks a stark contrast with the brighter and more neutral tones of the first six paintings, all of which have two-color shading, reminiscent of the painting in the collection of the Austrian Ludwig Foundation. The final four painted canvases are monochrome, so that the wave shape flattens, appearing less like sinuous undulations and more like vibrating or pulsating discharges of electrical energy.25 In the eyes of critic Kasha Linville, in the last two paintings the waves become “visually dematerialized by their dense waviness”; the colors are “shinier, darker,” and the surfaces “soft, splotchy.”26 By Lozano’s own admission, the color of these last paintings is “decadent.” She found that the deep maroon of 48-Wave and the purplish silver of 96-Wave gave hints of high-energy color, a literal reference that she usually tried to avoid but this time “just couldn’t resist.”27 The decision to do away with two-color shading was in part pragmatic, since the textural application of paint required her to work wet-on-wet over longer, more grueling painting sessions. To paint 96-Wave, she worked continuously over three days.

In physics, a wave refers to a “period disturbance in a medium or in space” whereby “energy is transferred from one place to another by the vibrations.”28 For Lozano, the energy that the Wave series carried from its place of production to its place of reception was akin to a psychic disturbance, or an intensity of feeling not dissimilar to a psychedelic experience. She noted “intensity” and “passion” as, together, a “high form of energy,”29 and she kept detailed logs of the joints she smoked while painting, joking that she had “put acid in these paintings, metaphorically.”30 At the Whitney, Lozano insisted on showing the paintings spotlit against black walls to make the point that the Wave series was “an attempt to take people out there.”31 Next to them in the gallery were supplementary notes and drawings along with two idiosyncratic props: an unstretched cut-out from a discarded version of the 6-Wave painting, which was suspended from the ceiling so that visitors could touch it, and a clear plastic box with birthstones and bodily residues such as nail clippings and hair.32 At the time, Lozano remarked that artists were “bringing more of their personal life into work/publicity.”33 By collecting these organic materials in her loft and framing them as The Me Pieces, she was perhaps experimenting with nonrepresentational ways of channeling her embodied experience into her own work.34 A heavily annotated copy of the exhibition’s press release was on display, too, with Lozano’s biographical information crossed out and only her date and time of birth offered as her “identity.” In its eccentric reference to astrology—or the forecasting of the effects of cosmic energy on a person’s life—Lozano’s odd reliquary reminded exhibition visitors that the invisible vibrations depicted in the Wave series also have bodily effects, just as the growth of hair and nails depends on exposure to UV radiation.

Back in 1968, at the time of the eclipse, Lozano noted that she “yearned to absorb with [her] body the moon’s force of gravity and the moon’s motion around the earth, and especially the force of earth’s gravity exerted on the moon.”35 In 1970, when she was working toward the Whitney exhibition, she voiced once again the hope that one day “we would be able to feel with our bodies the laws of physics. As supersensitivity increases, why not? Feel gravity waves, feel the mathematical relation between matter & energy.”36 By then, however, she was less certain about the capacity of painting to convey this cosmic sense of motion, change, and transformation. She painted many of the canvases in the Wave series while immersed in what she called her “Life-Art” practice: a series of instructional scores begun in the spring of 1969, in which she set tasks for herself and followed up with recorded observations of their effects on her life and on those around her. As was the case with other artists in her circle, Lozano’s turn to conceptual art was sparked by her frustration with the institutional art world and its legitimation of a corrupt political system.37 But, for Lozano, the “Life-Art pieces” were also an effort at deconditioning. They were fueled by the belief that the art system was not exclusively sited in museums and galleries, but also internalized by artists.38 Challenging it required changing subjectivity.

Leaning against the walls of her loft between April and December 1969, the Wave paintings were silent witnesses to Lozano’s Dialogue Piece, a score that prompted her to invite friends and acquaintances to her apartment for the sole purpose of having a conversation, a free and even “joyous” exchange of ideas among artist peers. At its most ambitious, it was an attempt to replace the economy of scarcity prevalent in the art world with one of abundance, in the hope of nurturing a more equitable artistic community. To counter relations of ownership and rivalry, Lozano told herself to “deluge [her artist friends] with information. Douse them with info like you’d throw a bucketful of water.39 Information, here, is a cognate of the energy flows depicted in the Wave series: it is code for the sharing and exchange of art ideas, but more broadly it is a way of describing—and directly intervening in—the affective and intellectual bonds binding a community together.

And yet, by the time Dialogue Piece came to an end, Lozano’s ambition to foster freer exchanges of ideas had been “wiped out,” together with “the goal of the sixties.”40 The picture that emerges from her notes on Dialogue Piece is one of information coveted and traded, often withheld and rarely gifted. “Few dialogues turned out to be joyous, or even social. Some were dull, some were nightmares of tension or discomfort,” she noted.41

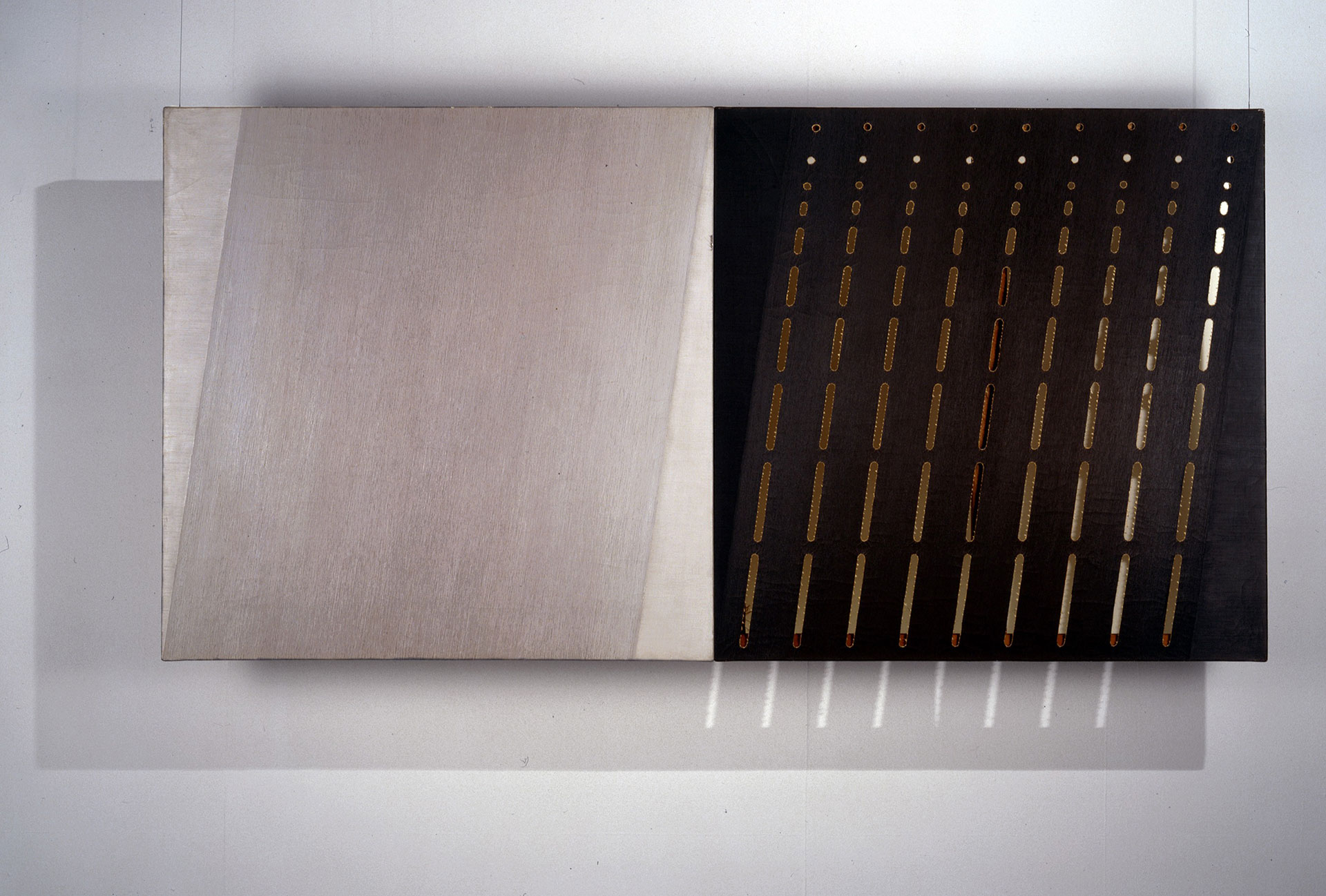

fig. 10 Lee Lozano, Punch, Peek & Feel, 1967–70, oil on canvas with perforations, 243 x 107 cm. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Whereas initially Lozano had understood her “life-situation-art & painting” as complementary in the construction of a “high-information field/system,”42 this hope was unraveling by April 1970, when she wrote Dropout Piece: a score that aimed at the “destruction (or at least complete understanding) of powerful emotional habits,” as well as the determination to “fight programming to work, to ceaselessly make $, to feed Daddy his ret’n, to achieve, to compete, to win.”43 This impulse also led to the puncture, if not total destruction, of some of her works from 1967, made in the period of transition between her paintings of abstracted mechanical parts and then waves. Shortly after writing Dropout Piece, Lozano sent one of the paintings she had exhibited in Cincinnati to a group exhibition at the Reese Palley Gallery in San Francisco—only this time with a string of holes cut out to bisect the central arched band in the original painting.44 She retitled the work Punch, Peek & Feel (fig. 10), which suggests that she wanted viewers to engage with it not just as visual surface but as part of a surrounding environment: they could peek through the holes to consider the work’s materiality, and they might touch its dangling, punched-out rounds. That same month, she drew up a study for cutting a pattern of holes out of one of the two panels of Stroke (1967), the last of the 1964–67 paintings she titled after verbs.

fig. 11 Lee Lozano, Stroke, 1967–70, oil on canvas with perforations, 106.7 x 213.4 cm. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase through the generosity of The Judith Rothschild Foundation and the Michener Acquisitions Fund, 2001.82. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

In the revised work, which she refers to in her notes as Stroke & Streak (fig. 11), nine identical sequences of perforations run down the length of the slanted black band of the original, each beginning with three cut-out circles and progressively extending into elongated, rounded rectangles. Lozano stipulated that the painting be hung about half a meter out from the wall, allowing the diagonal perforations to cast “streaks” of light onto the partly shaded wall behind, like negative brushstrokes.45 While there is no denying the aggression implicit in cutting holes into her earlier paintings, these are structured, calculated interventions that align with and expand on the original compositions rather than shattering them. Perhaps Lozano was reanimating the transitional thrust of her paintings. Whereas in 1967 they had nudged her toward the wave form, she was now piercing them to look for ways to push painting out into the world.

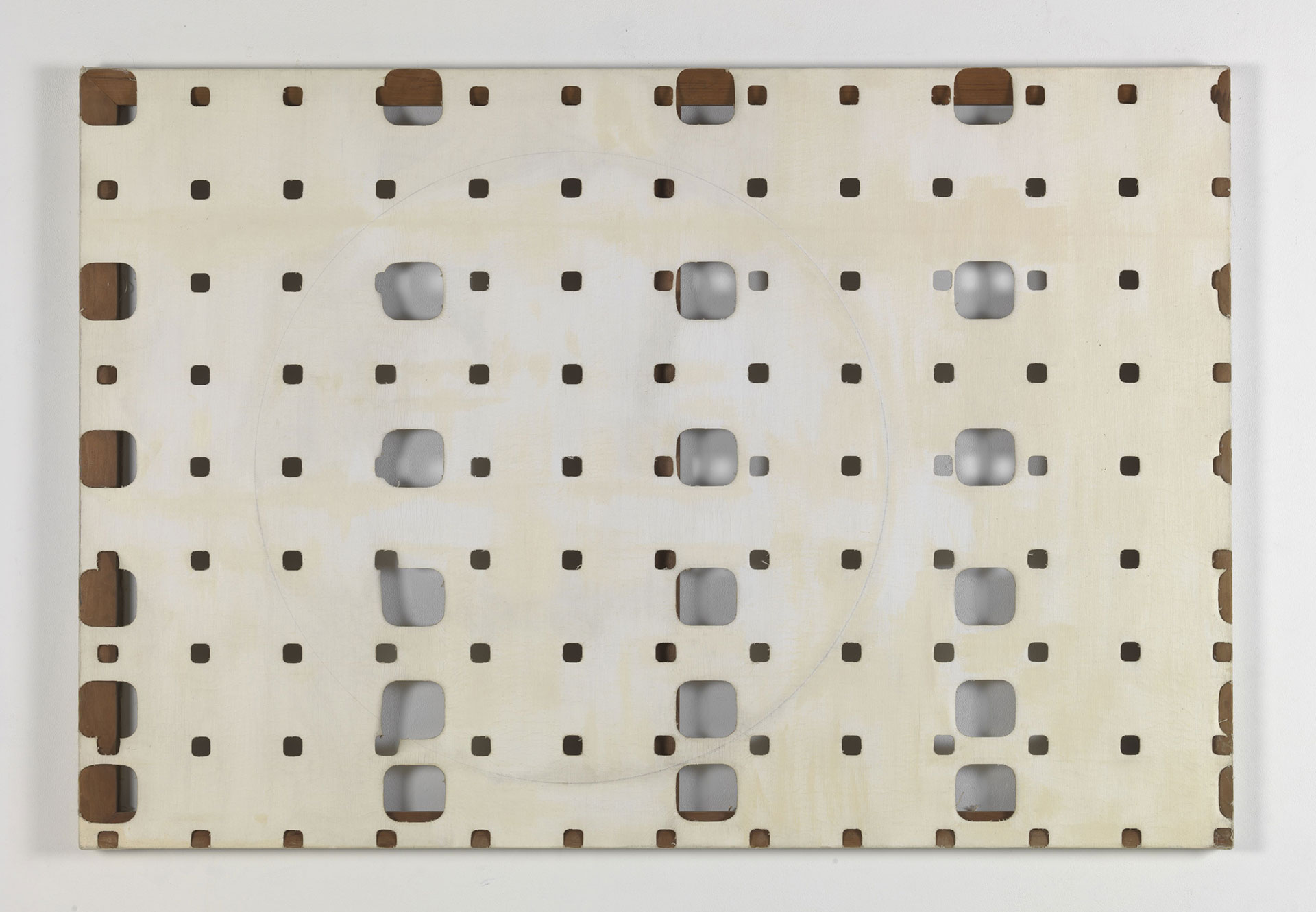

fig. 12 Lee Lozano, No Title, 1970, gesso and graphite on canvas with perforations, 107.4 x 157.6 x 3.9 cm. Collection Hauser & Wirth, Switzerland. The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

“As soon as I complete the drawing of a circle, I wish to be outside of it.” Lozano added this line from Buckminster Fuller to a graphite study for a 1968 four-panel painting of a segmented ring.46 It was only after she determined to step out of the art world in 1970 that a full circle would appear in her paintings, barely sketched in graphite on a gessoed canvas (fig. 12), like the uncertain lines of 192-Wave, the last of the Wave paintings, which she would draw by the end of that year. The effect is different from the two untitled paintings of 1967 where the semicircle radiates energy. Here, the faint circle is mere ground for the most spectacular of Lozano’s hole patterns: two overlaid grids of rounded-square cut-outs, recalling a punch sheet. Back in 1968, she framed her paintings of semicircles as a means of focusing on “the energy which emanates from the forever conflict in painting between the second dimension of its object-space and the third dimension of its implied space, or … its static solid-matter surface and the passages of movement and time it evokes in the mind.”47 Now, this aspiration to roundness had been turned inside out; the only passage implied in this punctured circle is an exit from painting. Total eclipse.

The author would like to thank Manuela Ammer, Bettina Brunner, Jaap van Liere, Rebecca Roman, and Perry and Lori Brandston for their help in researching this essay, as well as Briony Fer and Jo Applin for continued support.

Copyediting and proofreading: Deirdre O'Dwyer